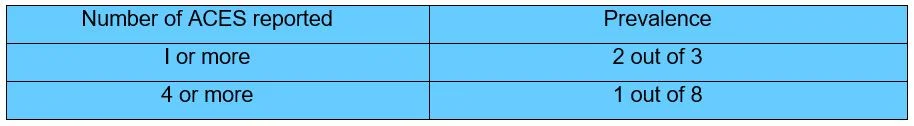

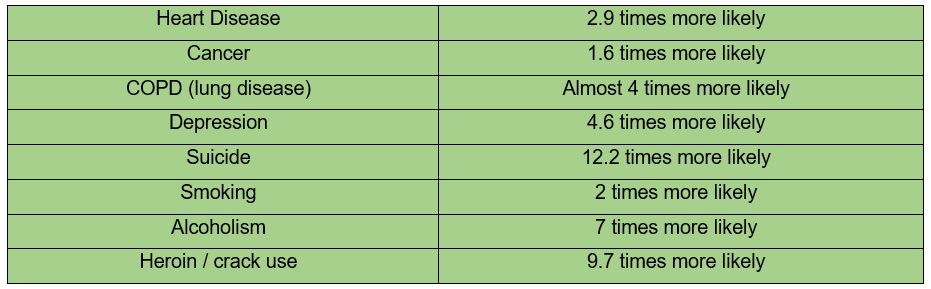

N Ireland has the highest suicide rate in the UK. An average of 5 people die through suicide each week. More people have died through suicide since the Good Friday agreement than died throughout the NI conflict.

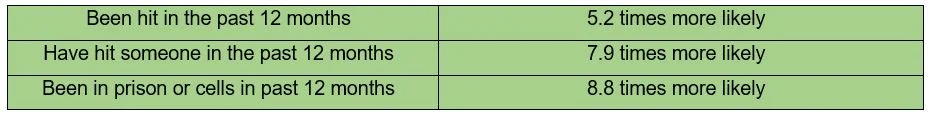

We have 25% higher overall prevalence of mental health problems than England and the highest rates of self-harm in the UK. Of 30 countries involved in the World Mental Health Survey, N Ireland had the highest rates of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Drug-related deaths among males in N Ireland (which account for 74% of drug-related deaths) have almost doubled in the last 10 years. Homelessness is increasing and more than 200 people have died while on the homeless register in Northern Ireland within 18 months.

The long awaited Suicide Prevention Strategy - ‘Protect Life 2’ was published today. The strategy sets out what the Department will do to reduce suicide and self-harm over the next five years and looks at the importance of everyone working together on prevention.

It is yet to be seen whether this strategy can meet its objectives, but one thing is for sure - too many lives have already been lost through suicide as well as through drugs and alcohol. We have known too many people through our work and our personal lives whose lives have ended prematurely and they are part of the reason Connected for Life came into existence.

Too many of people in our community are living without hope, choice, belonging, opportunity & connection. Rather than sighing with resignation at this situation, we should be outraged! They are our fellow human beings, they belong to us and we to them. It’s not just the role of mental health services, politicians and policy makers to protect lives, it is a collective responsibility in which we all play a part.

It is all too easy to live in our own bubble and try to ignore the pain and suffering in our society. It is easy to look the other direction in the face of human suffering and to console ourselves with the idea that those experiencing poverty, homelessness or addiction have arrived in that place due to making poor choices and are therefore less worthy of compassion. When children in our communities are engaging in anti-social behaviour or using alcohol / drugs it is too easy to blame the parents or to be one the 35% of people in N Ireland who believe paramilitary attacks, including those against children, are justified. It is all too easy to judge, shame and dehumanise our neighbours when they are most in need of understanding, compassion and connection.

Many professionals working within the field of trauma experience frustration at the limitations and flaws in our systems and how they can even cause further harm. Sometimes it is easier to climb into that bubble again, just get on with it and ignore the bigger picture. We can become so enraged by the flaws in systems that it impacts our own well being and impairs our ability to work most effectively. Rather than bemoaning the toxic systems we work within, we should focus on the difference they do make, do everything in our power to highlight their limitations and do what we can to change them, while looking after our own well being in the process.

One of the reasons we have such high rates of suicide and mental illness is the legacy of the conflict. 39% of the population experienced some sort of traumatic event during the conflict. While others did not directly experience a traumatic event, the experience of living among so much violence and potential danger can potentially impact us all, changing our biology, producing brains and a stress response system primed for danger. These changes transmit to the next generation through epigenetics. So not only are we a collection of traumatised as individuals, but we also live in traumatised communities and work in traumatised organisations. This makes ‘othering’ common within our communities and organisations, making it more likely that communities will turn against those they see as weak or dangerous and that organisations become competitive, rather than collaborative.

This is why we are passionate about building a trauma aware, sensitive, informed and responsive community in Northern Ireland. We need to become trauma aware as individuals, organisations, community and a society. We need to support those impacted by trauma by providing effective services and environments, supported by effective policies and strategies. We need ensure we do not re-traumatise people through judgement, shame and oppression personally, in our organisations, in our communities and as a society. We need to build a community and society that is compassionate, connected, nurturing, vulnerable and forgiving and that values every individual. This is a long way off and we have a lot of healing to do before we get there but we if we all play our part and acknowledge our collective responsibility healing is always possible.